There used to be an expression heard in San Giovanni in Fiore, and the other little Calabrase mountain towns near the arch of the boot in southern Italy that have West Virginia coal-mining connections.

People would say it when they were on their way to an errand, or work, or just an outing with friends.

Paraphrased, it went: “Don’t worry. I’ll be fine. It’s not like I’m going to Monongah.”

In other words, the loved one leaving through the front door at that moment fully anticipated safe travels and a routine return.

And yes, they were referring to that Monongah in neighboring Marion County, the site of one of the deadliest deep-mine disasters in the U.S and world.

On Dec. 6, 1907, a series of deadly explosions were set off when a runaway coupling of coal cars snapped power lines to the mine.

Up to 500 workers died, many of them boys, working underground, underage.

A sad, sizable roll call of victims hailed from San Giovanni.

And many of their descendants, plus those of the other San Giovanni sojourners who lived to tell about it, stayed to persevere on these shores.

That mining history, grim as it can be, serves as only part of north-central West Virginia’s Italian-American experience, however.

That the ensuing generations are still here, and still celebrating their lineage, was in part why Patrizia Monti, Franca Riccardi and Paula Bonavitacola were also here last week.

Understanding, really

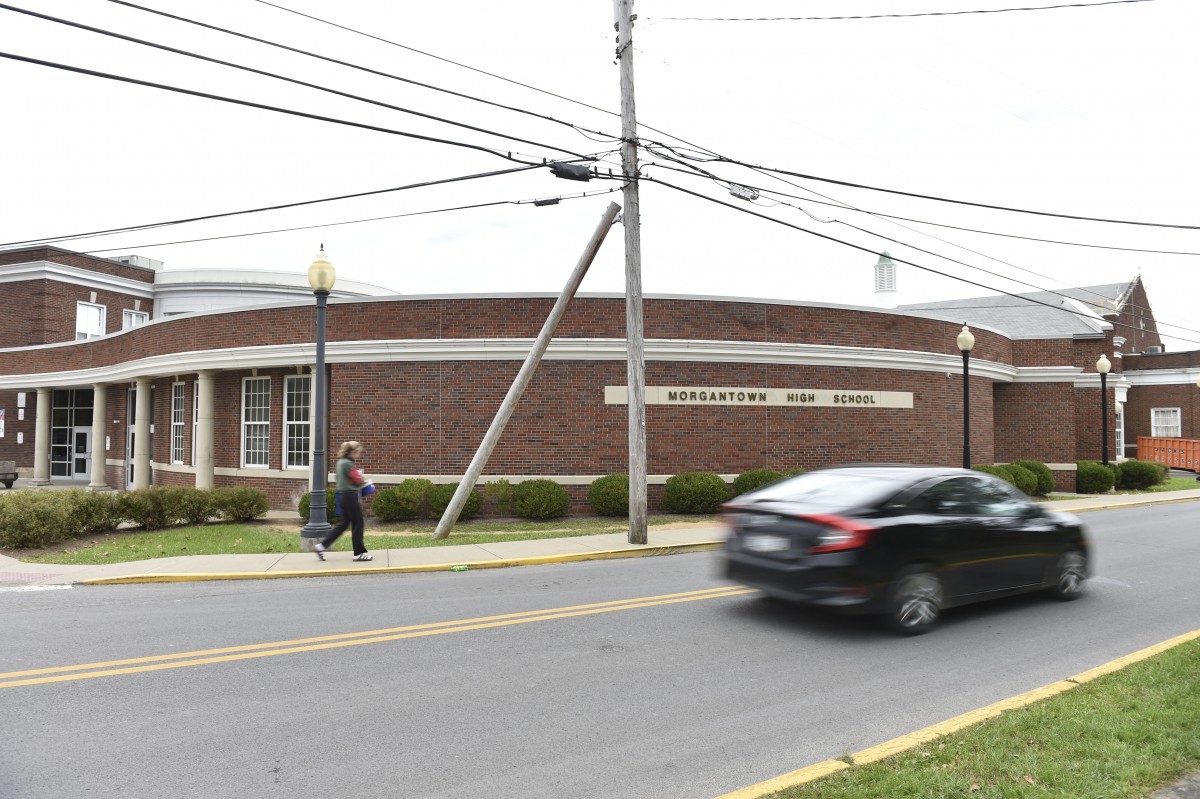

The teachers and administrators called on Adrian Kiger Olmstead’s classroom at Morgantown High School.

Olmstead teaches Italian at MHS. She’s fluent in the language, having lived in Italy for few years before returning to her hometown of Morgantown.

Monti directs the education office of the Consolato Generale d’Italia (Consulate General of Italy) of Philadelphia.

Riccardi is with the consulate’s American-Italian Society, serving as that organization’s director, also.

Bonavitacola is board president of the outreach group, Filitalia International, also headquartered in the Pennsylvania city.

The consulate’s territory takes in an expanse from New Jersey to North Carolina. The trio regularly travels that territory, looking in on schools that offer instruction in Italian.

U.S. students taking Advanced Placement courses can also apply for Study Abroad programs in Italy.

Mon’s school district is the only one in West Virginia to offer language instruction in Italian, said Olmstead, who also teaches that subject at South Middle School.

Her classes aren’t brow-furrowing exercises in verb conjugation and outdated expressions repeated by rote, she said.

“I just get them talking.”

Like all teachers, she enjoys seeing students who suddenly discover, often all at once, that they’re fully, actually understanding what was being said.

“I was the same way,” Olmstead remembered. “I want them to have fun in my classes. This doesn’t have to be a chore.”

At MHS, her students include a beginner and a bit of ringer.

One of the beginners is Anthony Kennedy, a junior who began online study of Italian over the summer and decided he wanted to delve in deeper.

“Sometimes I can pick out a phrase,” he said, grinning. “Which is amazing for me.”

Sofia Doretto, meanwhile, laughed at that “ringer” designation bestowed upon her by a classmate.

“Come on, I can still learn,” she said.

Even if she is fluent in the language.

Her parents left their native Italy years ago for education and work in the States.

Like Olmstead and the class visitors, she too switched back and forth from one language to the other.

For her, the challenge isn’t thinking and speaking in the moment. It’s sitting down and writing formal papers in the language of her parents.

“The grammar is completely different,” she said.

Mangia, mangia

And some things are completely universal.

The visitors were served lunch, mixing Italian and American fare.

Pesto Focaccia sandwiches and an autumn salad blend with apples, cranberries and pecans.

Pumpkin pie and apple pie.

When the food came out, the dynamic changed a bit — as it always does.

Everyone broke bread.

Anthony continued to make inroads.

Sofia continued to translate.

Conversations, as said, were in Italian, English and combinations thereof.

Picture a bilingual seminar, featuring social discourse on the immigrant experience and capsule examples of tolerance and intolerance — all taking place in your Nonni’s kitchen.

Monti, a professor who taught English in her native Italy before signing on for international work with the consulate, was right at home. She wanted the Morgantown students to feel the same, wherever life and their passports may steer them.

“When you learn a language, you begin to have an awareness of a society,” she said.

“When you have that awareness, you also begin to have empathy. Then, you gain tolerance and understanding.”

TWEET @DominionPostWV