MORGANTOWN — Center-based child care costs rose by 12% overall in West Virginia during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a report released in September by the Center for American Progress.

Increased staff salaries, additional sanitation supplies and personal protective equipment that came as a result of compliance with CDC guidelines are reasons for the increase.

West Virginia spent $1.25 billion of the CARES Act funding it had received as of March 8, and a portion of that offset the cost to parents and child care centers. Still, parents and centers aren’t unaffected. The state is looking to receive another $1.259 billion from the American Rescue Plan, and $260 million of that is earmarked for child care.

Sharon Portaro, director of the Presbyterian Child Development Center in Morgantown, said her center is buying cleaning supplies more often. Gloves were already provided in the day care for things like diaper changes, but because of the pandemic, they are more expensive now.

Portaro estimates the percentage of the budget that went towards cleaning supplies rose for the center by 15%-20%.

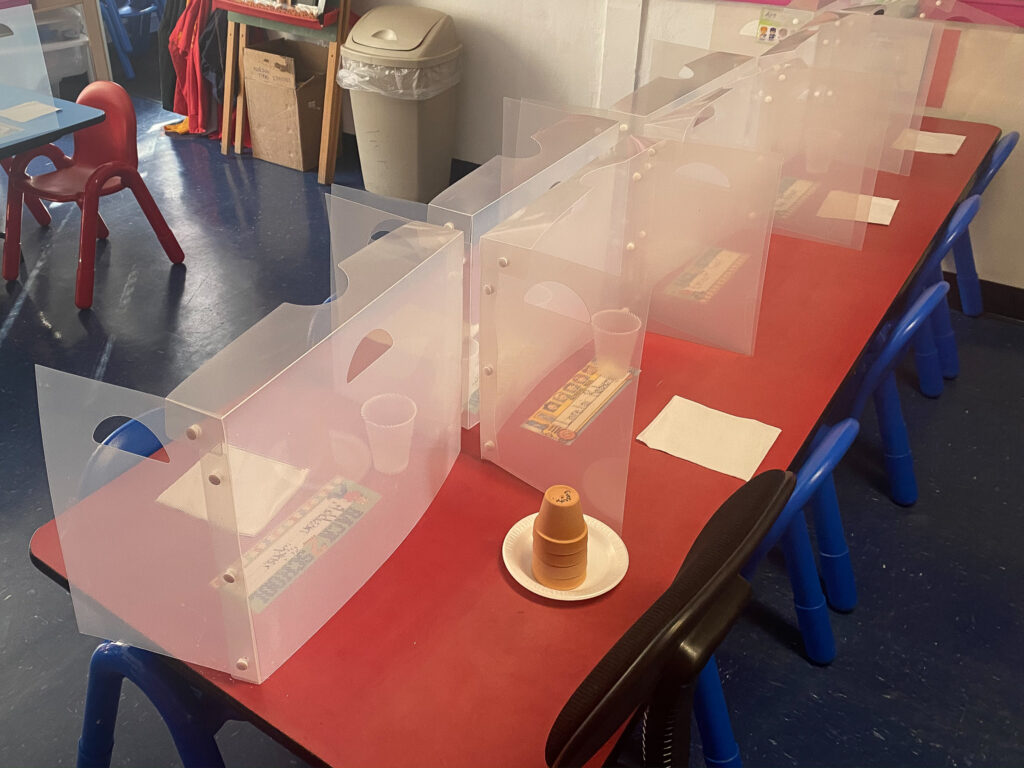

Additionally, the center has invested in separate materials for each child. These materials include art supplies and lap desks. Instead of using the water fountain, children have their own labeled water bottles to minimize sharing.

In classrooms where toys are shared, the toys are easy to clean. This means no plush toys. The toys are washed or sanitized and left to dry overnight.

Despite the precautions child care centers are taking to ensure the safety of children, Morgantown parent Renee Beard said she still thought that she was putting her daughter at risk of catching COVID, but she had to trust the day care because she couldn’t leave her daughter home alone.

Beard said her daughter, who is 11, went to day care to be supervised during online learning while she and her husband continued to work. Day care had not been part of their budget pre-pandemic.

Another parent, Ryan Wamsley said he was concerned about the number of germs his daughter might bring home, but he had to return to work.

Wamsley said at his daughter’s day care they have a “yuck bucket.” This is where the center places everything that has made its way into a child’s mouth, so it can be cleaned before being used again.

Joseph Lawson is a county environmental health specialist, who inspects child care centers for the Department of Health and Human Resources. He uses a checklist to make sure the facility has plans for absent staff, adequate staff to child ratio, parent dropoff, pickup procedures and screening for children upon arrival.

He said though there is a rigorous safety standard to which centers have to agree, a lot of parents have still kept their children away. Some don’t need child care because they are working from home. Lawson said that loss of revenue has cost child care centers.

In March, he said the loss of revenue was why some centers were barely making budget, and he knew of at least one that was on the brink of closing.

Upon any COVID-19 exposure, businesses are required to shut down to minimize the potential spread. Bobbi McClelland, owner of Storybook Daycare, said it’s frustrating that the health department staff can’t get on the same page. She said she had been advised by two people on a one occasion to close down for a different number of days. On the days closed, her center lost revenue.

Beard said when her daughter’s facility quarantined, she was able to take her daughter to work with her, which was fortunate, because she wasn’t able to leave her with family because they didn’t want to be exposed.

Portaro said guidelines for quarantining upon a COVID exposure can cause the center to be short-staffed. In January, one positive case in her facility led to six staff members being out.

McClelland said her center has a “good system” for staff as far as scheduling goes as long as COVID doesn’t come into play. When staff members are out, she said her center alters hours to make sure she isn’t overworking the rest of the staff.

Despite a loss of clientele in some cases, centers have had to add staff.

McClelland had to hire another person solely for the increased sanitation procedures Storybook is required to follow.

Adding people to the staff increased the costs of the operation, but McClelland acknowledged that child care in Morgantown is hard to come by, which has ensured the success of her business.

She said she has been asked by parents about putting more kids in her care, but it has been difficult to hire additional staff to accommodate these requests because the salary she can offer can’t compete with the unemployment benefits people received during the pandemic.

Portaro managed to keep her full-time staff throughout the pandemic, but she lost all of her part-time staff when WVU closed and sent students home last spring. She has only added one part-time staff member back.

Extra staff is one of the things that has increased the cost of care. Though child care is costing more, the state is subsidizing the costs for centers and parents.

Wamsley’s family was able to receive free child care through West Virginia’s assistance program. Wamsley said this program allowed the family to put money typically budgeted for child care towards savings.

Portaro said many people like to brush off child care workers as an afterthought, but without them a lot of people couldn’t earn a living.

“They can’t go to work if they don’t have a place for their kids to go that is safe, affordable and available,” she said.

Ciara Litchfield is a student in the WVU Reed College of Media. This article was written as part of the multimedia storytelling capstone class and offered to The Dominion Post for publication.