MORGANTOWN — Standing at the confluence where a tributary feeds into West Run, Dr. Jason Hubbart motions to the right where flowing water appears milky-white. He motions to the left, where deep red and orange sludge covers every crevice in the stream.

The only visible living organism is a tuft of red algae clinging to a rock.

“Some people say, ‘Wow, that’s beautiful. Look at those colors.’ And I’m like, ‘What do you think does that?’ ” said Hubbart, director of the Institute of Water Security and Science at West Virginia University. “And then somebody knows the answer.”

It’s all acid mine drainage.

Acid mine drainage, or AMD, is water that has become polluted due to mining activity, making it highly acidic and rich with heavy metals. AMD can cause water to be highly toxic and is detrimental to aquatic life and potentially harmful to humans.

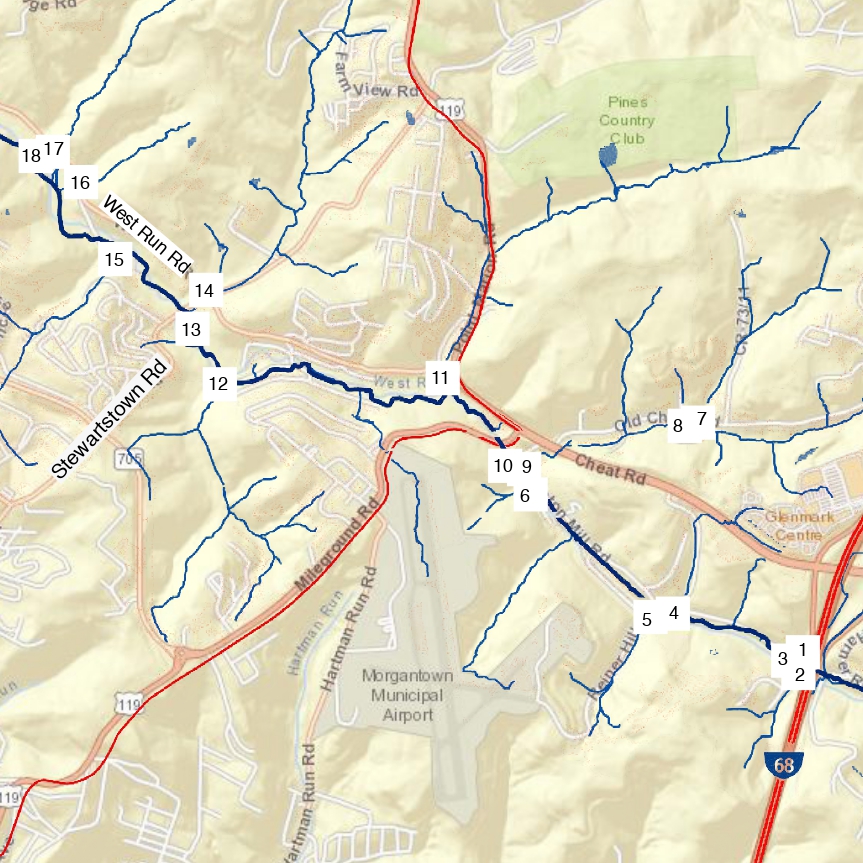

The location described above is just one of 22 monitoring stations Hubbart has installed throughout the West Run Watershed. Through these monitoring sites, Hubbart studies the issues the watershed faces, the issues it will likely create, and what it will take to prevent the situation from worsening.

Tracking acid mine drainage

Hubbart has recorded pH balances as acidic as 2.7 at some monitoring sites. Excellent water quality is considered by the WVDEP to be between 7.6 and 9.0. Anything below 6.0 is considered to be poor.

“By the way, stomach acid is two,” Hubbart said.

Although some species can survive in water with more-acidic pH balances, most aquatic life thrives in waterways with a pH balance of about seven. At site five, near the Morgantown Airport, Hubbart has witnessed firsthand some of the destructive impacts low water quality can have on wildlife.

“I’ve found three-legged frogs out there,” he said.

Terry Fletcher, West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection acting communications director, said AMD in the West Run Watershed originates from several surface and underground mines in the Pittsburgh and Redstone coal seams that discharge into the watershed.

Fletcher said all coal mining in the watershed was conducted prior to the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, with the exception of one permitted surface mine that has been completely released.

Because of this, there is no continued reclamation responsibility for the mining company or the landowners.

Further downstream, near the intersection of Stewartstown Road and West Run Road, there is evidence of what Hubbart believes to be another root of the problem. West Run is home to several housing developments and more are under construction. As developers dig into the bedrock to create housing foundations, iron ore is released into the stream.

Pollutants are not the only concern Hubbart has when it comes to construction in the area. After developments are built, a new problem arises.

Runoff and the threat of flooding

In the field southeast of Stewartstown Road — part of the university’s farmland — flooding is common, but Hubbart said with every new construction, the situation will worsen.

“… If we don’t do something here, that bridge is going to wash out,” Hubbart said of a small span on Stewartstown Road. “Or, before that, likely what’s going to happen is it’s going to flood the property of the landowners on the other side of the road. And then we’re really going to hear about it.”

Hubbart said increased runoff is one of the main contributors to erosion and as the walls of the watershed rapidly degrade, the stream grows with it. This erosion has occurred so quickly that the stream has more than doubled in width since 2016.

Signs of Hubbart’s prediction have not gone unnoticed by local businesses. Salon 360 has resided along the watershed for about six years, but it wasn’t until a year and a half ago flooding entered the building for the first time.

“We had a flood where it actually came into the shop when we were in the small building, and it flooded the whole building,” said William Rutherford, owner of the salon. “It’s kind of progressively gotten a little worse over the years, but it only usually happens when we get quite a bit of rain.”

Rutherford said minor damage was caused by the flood, including equipment getting wet and damage to the floor’s paint. The flood eroded soil from the stream, carrying away asphalt from the parking lot.

Salon 360 has since relocated to the building next door, where Rutherford said he feels more at ease considering it is higher in elevation. Shortly after the flood incident, Martin Biafora opened the BC Jerk Pit in Rutherford’s previous location.

Aware of previous issues with flooding in the area, Biafora said he worked with the landlord to install a barrier to help prevent future flooding. He said he feels taking preventative measures is one of the only viable options, as he has doubts fixing or stopping the issue is possible.

“It’s kind of too late to fix it,” Biafora said. “The water is coming because of what’s been done. It’s got to go some place.”

Looking to the future

Although a daunting task, Hubbart believes not all hope is lost for improving the watershed.

“It takes hundreds or thousands of years for this to stop,” Hubbart said. “But, there are things you can do to remediate it.”

The land in the watershed is owned by multiple landowners, primarily West Virginia University. April Kaull, executive director of Communications and University Relations with WVU, said the university first became aware of the situation in December of 2019 and has been in communication with the WVDEP to discuss potential solutions.

“We take very seriously our stewardship of the land that comprises the West Virginia University System, including the West Run Watershed,” Kaull said. “After we became aware of concerns on the property, our Office of Environmental Health and Safety contacted the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection to assess the situation.

“We will continue to work with the WVDEP and may consider other potential mitigation measures based on expert analysis and advice.”

Keeping the area in check and understanding how the waterway can restore itself is where Hubbart’s monitoring systems come into play.

By monitoring the watershed, one thing Hubbart hopes to understand is the watershed’s bioremedial process, or how the watershed naturally treats contamination.

“Wetlands can remediate AMD effects also,” he said. “But, we don’t really have a good handle on what those processes are, how long it takes [or] what does that look like.”

Mitigating some of the issues within the watershed begins by pinpointing major problems and implementing a Total Maximum Daily Load, or TMDL.

A TMDL allows organizations to set a limit for how much AMD part of the river is able to flush out in a given period of time. The areas that overflow the TMDL are the areas that will need funding allocated toward them for additional treatment.

Fletcher said TMDLs have been completed in the West Run Watershed for pH, dissolved aluminium, total iron and fecal coliform. Relative to AMD, the TMDL identified 26 individual discharges from abandoned mine lands that were mined prior to the SMCRA.

Limitations come with implementing TMDLs in the watershed because of the SMCRA of 1977. The WVDEP is responsible for implementing TMDLs through the Special Reclamation program in former or active mines, but not those which came before the SMCRA of 1977.

Because of these limitations, no sites within the West Run Watershed fall into the WVDEP’s responsibility for implementing a TMDL.

Fletcher said previously, the West Run Watershed Association, WVDEP, WVU Water Research Institute, City of Morgantown and U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement collaborated to build a project to treat acid water emanating at the eastern portion of the Morgantown airport. This allows the water in West Run to meet water quality standards as it flows past the Morgantown Learning Academy.

However, no further improvement plans for the watershed exist that the WVDEP is aware of.

Taking into consideration what living near clean water means for a community, restoring and monitoring the watershed continues to be a priority for Hubbart.

“How would you like your water to look? Would you like it to look like that?” Hubbart said. “If it did look like you want it to look, would you have more pride in where you’re living? … Would you appreciate it more? Would you take better care of it?

“All those things would probably happen, but when you have to start with something that is so ransacked, instead, what I’m seeing is avoidance, cover it up because there’s nothing we can do about this. This is too overwhelming for me to deal with. And it is overwhelming. But we should get started.”

Audio editing by Chris Schulz

TWEET @DominionPostWV