MORGANTOWN – Bad roads cost money. Most obviously, repairs and maintenance are expensive.

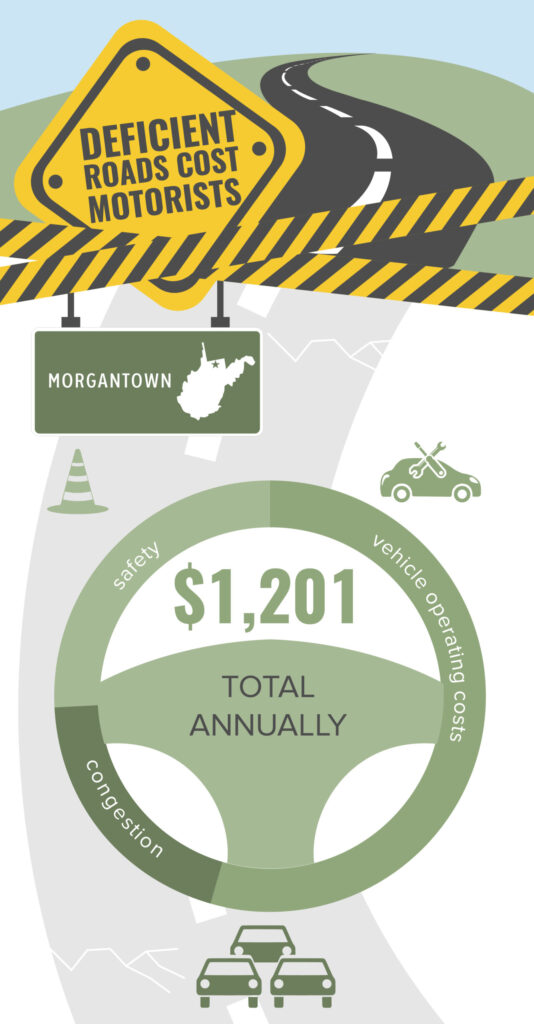

But a national nonprofit transportation research organization, TRIP, each year reports on the hidden costs to motorists: vehicle operating costs (VOCs) from rough roads, wasted time and fuel from congestion, and traffic crash costs from unsafe roads.

TRIP’s recently released 2021 report puts the total annual hidden-cost figure for West Virginia at $1.6 billion.

TRIP homes in on seven West Virginia metro areas in its report and the per-driver figure for Morgantown is $1,201 per year.

In order, here’s how the seven cities fall in total annual hidden costs: Wheeling, $1,421; Beckley, $1,299; Charleston, $1,280; Huntington, $1,273; Morgantown, $1,201; Weirton-Steubenville, $1,116; Parkersburg, $992.

Morgantown is by far the worst for VOCs, $654 per driver; Weirton-Steubenville is a distant second at $551.

It may be a surprise to those who’ve been stuck in WVU or manufacturer shift traffic, but Morgantown ranks a lowly fifth for congestion costs, at $238; Wheeling is worst at $572.

And Morgantown ranks sixth for safety costs, at $309 per driver; Beckley is worst at $597. West Virginia’s traffic fatality rate 13th highest nationally: 1.36 deaths for every 100 million miles traveled. The rate on rural, non-interstate roads is worse, 2,10 deaths per 100 million miles.

West Virginia’s Road Fund, for repairs, maintenance and construction, has remained stagnant for many years at about $1.1 billion while costs have escalated.

Rocky Moretti, TRIP’s director of policy and research, reminded press attending the announcement of the report that in 2015, the governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Highways said the state needs an additional $750 million per year for maintenance plus another $380 million annually for needed expansion – essentially doubling the current cost.

The governor’s 2017 Roads to Prosperity program made a dent in that, he said, devoting $1.6 billion through voter-approved bonds for new construction and, it was hoped, freeing up Road Fund money for maintenance and repairs.

COVID-19 took a toll on the Road Fund, he said. It’s fueled by fuel taxes and when the pandemic hit travel fell by 40%; around November that improved but travel remains about 11% below average.

Transportation Secretary Byrd White talked about challenges of getting West Virginia’s 34,420 miles of state-maintained roads up to snuff. “We’re behind. We’re trying to chase and catch up to problems that have been here for decades,” he said.

The bond program is funding new construction, he said, and the Division of Highways is trying to get back to do preventive work: keeping water off the roads through ditching; patching potholes before they get too big; doing canopy cutting to keep the roads dry.

The results won’t be immediately evident, he said. “But we’ll see that over the years.”

Deputy Transportation Secretary Jimmy Wriston commented on what he called the overriding message of the report: “It outlines the cost of doing nothing.”

Roads to Prosperity alone isn’t enough, Wriston said. “We need a big, bold vision out of Washington.”

The five-year federal surface transportation bill isn’t really a vision, Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, R-W.Va., told The Dominion Post on a different day. It provides the money so governors across the country know their funding formulas and can develop their sate plans.

The current federal package, the FAST Act, expired in 2020 but Congress extended it through Sept. 30 this year, the TRIP report says. West Virginia received a total $2.8 billion through FAST, about $465 millon per year for road repairs and improvements.

Capito is ranking member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee that is crafting the bill. She said during the press conference, “A bipartisan highway bill is certainly one of our biggest goals.”

Pavement and bridges

TRIP also looks at two other issues: pavement conditions and bridge deterioration.

TRIP says that statewide, 55% of all major roads are in poor or mediocre condition, based on Federal Highway Administration data: 31% poor, 24% mediocre.

Of the seven metro areas, Morgantown has the most poor roads, at 30%; it’s sixth for mediocre roads at 18%; tied for second best for fair roads at 15%; and dead last for good roads at 37%.

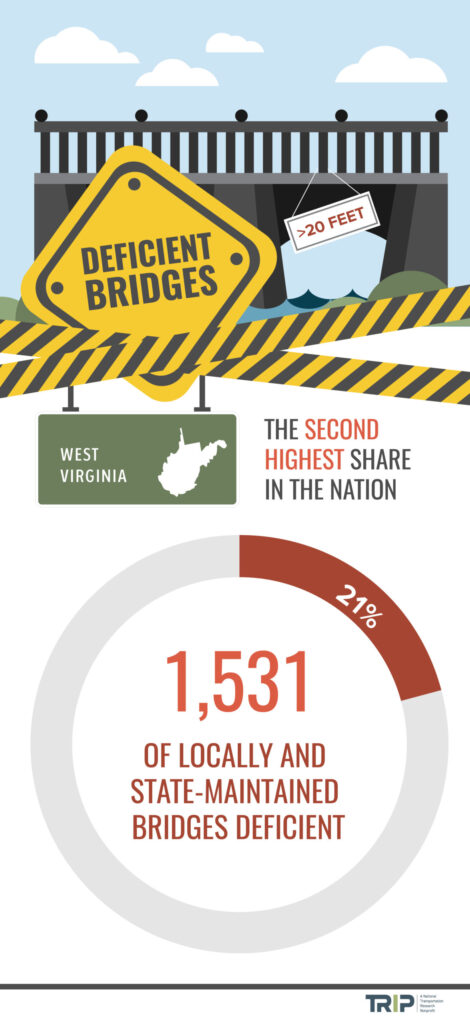

West Virginia has 7,291 bridges of 20 feet or more in length, TRIP says, and 1,531 of them – 21% – are poor or structurally deficient. That’s the second-worst rate in the nation. Fair bridges come in at 53% and good bridges at 26%.

Structurally deficient bridges, TRIP says, may be posted for lower weigh limits or closed altogether.

Based on share of bridges, Morgantown ranks second-worst for the proportion of poor and structurally deficient bridges at 20%; Beckley is worst at 23 percent. Morgantown is fifth for fair bridges, at 43%, and fourth for good bridges, at 37%.

Looking at sheer numbers, Morgantown has 204 bridges; 40 are poor or structurally deficient; 88 are fair; 76 are good.

Tweet David Beard@dbeardtdp Email dbeard@dominionpost.com