Picture the Hough Park swimming pool in Mannington, Marion County.

It’s one of those glorious, Technicolor summer days in the middle of the 20th century.

Marco Polo and cannonball splashes.

Pretty girls who really, really don’t want their hair wet.

Their would-be suitors, showing off with diving-board contortions that won’t garner any Gold on this afternoon.

Laughs, whoops and the shrill-trill of the lifeguard’s whistle.

At the edge, he’s easy to spot: A smallish, wiry kid, with his fingers laced in the steel weave of the cyclone fence.

Well, check that.

Dude’s more scrawny than anything, as he’s all elbows and knees.

Going back and forth with his buddies, he’s whooping and laughing, too.

Except, he’s on the other side of the fence.

“Ronnie! Why ain’t you in here with us?”

“Can’t. Not allowed.”

Which was the picture of institutional racism in 1950s America.

It was also the gossamer beginnings of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dream.

A towering oratory born of wistful, fragmentary images of little white kids and little Black kids, simply playing together, just because.

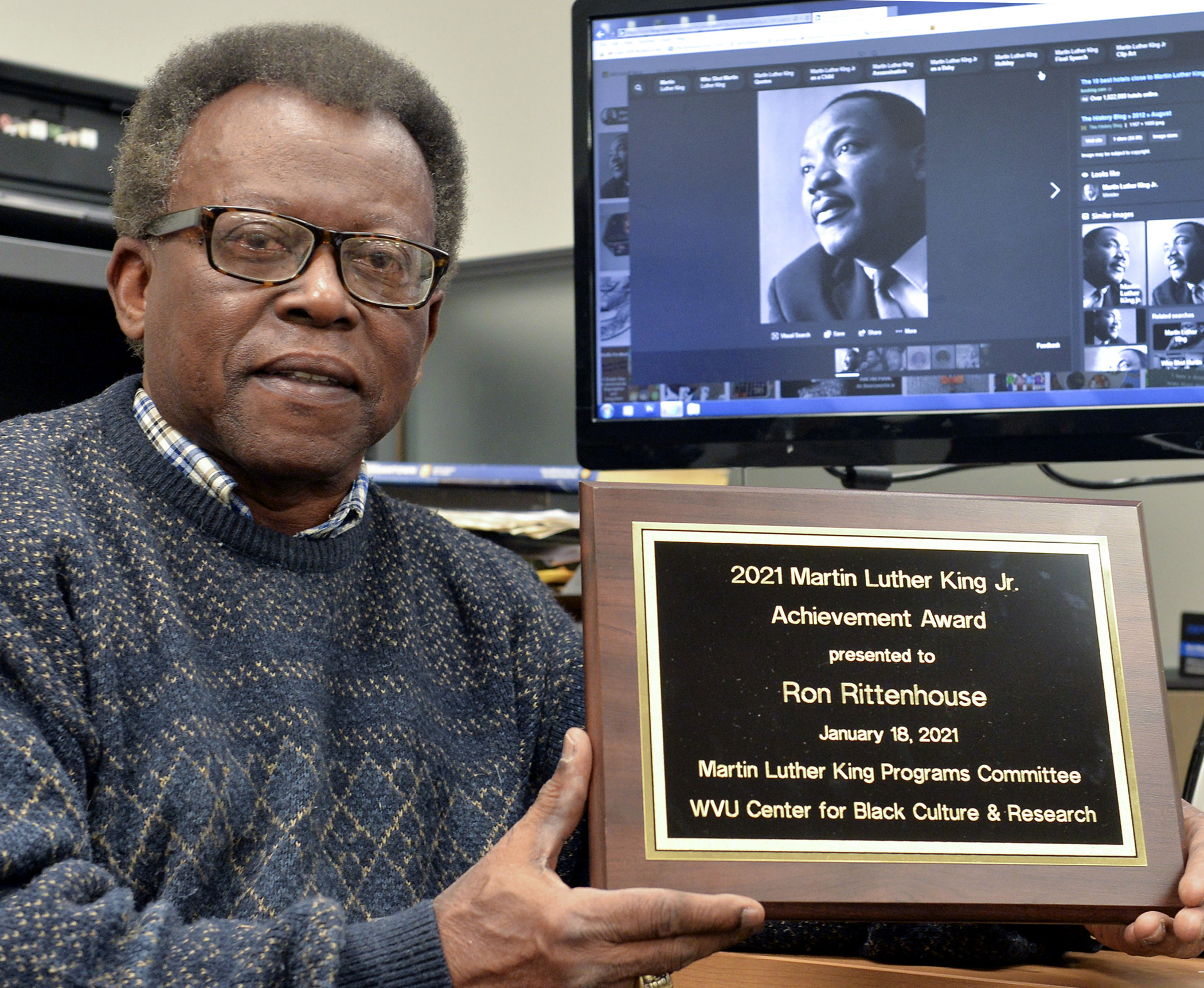

Ron Rittenhouse shakes his head and gives a little grin at the unspooling.

“That’s just how it was then,” the chief photographer of The Dominion Post said.

Last week, WVU’s Center for Black Culture and Research focused on who Rittenhouse is now, recognizing him with its MLK Achievement Award for 2021.

The award, the center said, best typifies those residents of West Virginia who are keeping the Dream going, in whatever fashion.

Or, as the chief guideline reads, “Making a substantial contribution in the advancement of such concerns as: Civil rights, human rights, humanitarianism, social action and advocacy, civility, improving the human condition, acting as a change agent for an inclusive and equal society for all people.”

The chief photographer who has seen everything through his lens — never saw this one coming.

“Are you sure you’re talking about me?” he asked.

“Absolutely,” answered Marjorie Fuller, the center’s director. “Who else would we be talking about?”

Back to the garden (and Morgantown)

If you live or work here, you see more diversity than most Mountain State dwellers.

College towns have a way of doing that.

When Rittenhouse was hired here in 1969, though, he was one of just two Black photographers working for newspapers in West Virginia.

How did that happen? He simply asked for work.

“That’s all I did. All there was to it.”

The publisher gave the kid a chance.

Five years before, Rittenhouse graduated from Mannington High School, a young man not necessarily adrift, but one who was still trying to figure out what he wanted to do in life.

He pulled a 1-A for the draft board, but amazingly didn’t get sent to Southeast Asia.

Rittenhouse was on his way to becoming a journeyman electrician and was working at Westinghouse in Fairmont when the light went on.

Factory life and junction boxes weren’t doing it for him.

The fledgling photographer quickly and happily went to work plying his new trade during that Aquarian year.

County commission meetings.

Kickoffs at Old Mountaineer Field.

Car wrecks (some gruesome).

Just as amazingly as not being drafted, he also scored enough vacation time for a long weekend that August.

So he cruised up to Max Yasgur’s farm and Woodstock in a sweet 65 Pontiac Bonneville with the word “HOUSE” (his nickname at the time) on a personalized plate on the front.

“I got to see a lot of hippie chicks,” he said.

“And rain and mud. And Jimi Hendrix.”

Over his 51 years at the newspaper, a lot of people have gotten to see a guy more about printing pictures than pigmentation.

Viewfinders of yore

Meanwhile, Rittenhouse, who is looking forward to his 76th birthday in March, has seen the summers of Watts and George Floyd in his lifetime.

He paid attention to what Dr. King was saying, and he will allow he’s been lucky — in that he hasn’t always experienced overt stings of racism over his life and times.

“When I was a kid in Mannington, I never saw color,” he remembered.

“I might hear the N-word, if I was out in the country somewhere, but then you’d have to consider who was saying it.”

He still gets called out — good naturedly — by many a mayor or other official who just have to make note when he sidles in.

That’s because he doesn’t always arrive on time.

News, you see — a house fire, a high-profile arrest — has an absolute disrespect of the photo schedule.

“Mr. Rittenhouse is here,” they’ll chortle. “Now we can get started.”

He still gets approached, even when he’s not working, and that’s because he’s part of everyone’s generational scrapbook.

A woman will remind him of the time he snapped her photograph at the Science Fair when she was 10 and how thrilled she was when it made the front page.

A man will talk about that shot of the barn his grandmother had on her refrigerator door for years.

Even when the paper started to curl and yellow, the man will marvel.

“I don’t always know them, but they know me,” he said.

“I guess if you stick around long enough. I appreciate it when they say hello.”

Fuller just appreciates a certain photographer.

‘A quiet giant’

With George Floyd and Black Lives Matter and media outlets in the middle of it all during a summer of unrest, Rittenhouse’s name quickly percolated to the top as the Center for Black Culture and Research was considering its MLK Achievement Award this year.

“Ron’s photographs are their own stories,” she said.

“They are accurate and fair representations of the news of the day.”

So too does she appreciate the time Rittenhouse takes with the students who frequent the center on Spruce Street.

While WVU is diverse, the students there are still in a decided minority.

“He’s a ‘quiet giant’ for social justice,” she said.

She’s just sorry the community won’t be able to be at the Mountainlair Monday morning.

The day of the holiday is when the center normally hosts its traditional Unity Breakfast, which includes the award presentation.

COVID-19 took care of all of that.

People can still watch a pre-recorded, abbreviated version, though, by visiting the center online at https://cbc.wvu.edu/.

That link will be available all day and for some time after, she said — just like a Rittenhouse photograph on a refrigerator door.

“The award is for Ron, his work,” Fuller said. “And it’s for who he is.”

Rittenhouse, in turn, appreciates the award — though, like Fuller, he’s sorry he won’t be able to interact with students on Martin Luther King Day.

“I can’t get over having my name in the same sentence with Dr. King,” he said.

“I tell those kids that they can achieve. They can accomplish anything.”

And that’s even if you come up on the other side of the fence at the Hough Park pool.

“You know what? Today, I’d just hop in my trunks and jump in.”

TWEET @DominionPostWV