West Virginia women key to ratification of 19th amendment

“Now what would you do in a case like this?”

That was the caption-question of a postcard that circulated across the U.S. in the late 1900s as the Women’s Suffrage Movement was gathering its own political ecosystem.

Playing to the patriarchy as it did, that mailing was hardly sympathetic to the cause.

It featured a cartoon depiction of a scowling man, done out in an apron and bonnet, giving his baby a bottle of milk.

The unspoken implication: His wife, the baby’s mother, isn’t home to cleave to her assigned gender role.

She wasn’t home — because she was out engaging in something that (as per the postcard) was utterly preposterous, for the social conventions of the time.

The little missus, it seemed, was showing the audacity of abandoning the hearth, so she could organize and fight for the right to vote, which was finally, fully recognized 100 years ago this month, in 1920.

That’s when the 19th Amendment, which established that privilege for all women, was ratified, after a 70-year battle — with lots of other skirmishes dating back to the founding of the Republic.

The unspoken question: Just who do these ladies think they are?

Colonial contradictions

Danielle Walker knows who they were — groups of women (and men, too) who were simply asking for all the rights and privileges therein, of living in the United States of America.

“I think about all that work that was done, and I want to celebrate it,” said Walker, who represents Monongalia County in the 51st House of Delegates.

“I also know we have a lot more work to do.”

Why? See above.

Like everything, it’s complicated.

That’s because discussions of gender equality are nothing new in the U.S.

The discussion even goes back to the country’s Colonial days, where inconsistencies — and contradictions, too — abounded.

That’s because women in the colonies of New York, New Jersey, New Hampshire and Massachusetts had already been afforded the privilege of voting — which lasted right up until the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, in 1787.

The founding fathers, still working off the manifest adrenaline of the Revolutionary War, gridded out the U.S. Constitution there.

When it was done, New Jersey was the only colony left where women had a civic voice, but they, too, where banished from marking ballots 10 years later.

Then came 1848, and the Seneca Falls convention in upstate New York, where the suffrage movement became just that: A movement.

Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth and other empowered voices wouldn’t let it be tamped down by the guys.

The March to the 19th Amendment was officially on.

Charted territory

Seneca Falls at least set the template, and by the time that postcard was making its rounds, the country was doing some steering of its own, as it set about negotiating paths around the patriarchy.

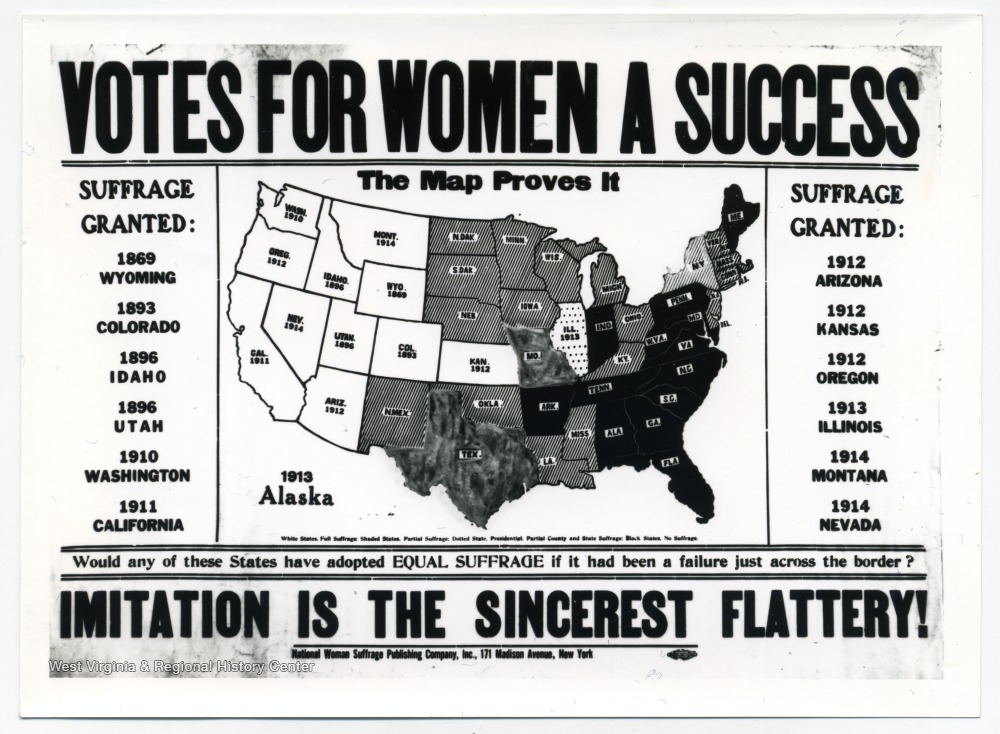

After the Civil War, women were voting in the Alaska, Wyoming and Utah territories.

Washington State, Colorado and Idaho, too.

They were casting ballots in California and Kansas, Arizona and Illinois, and North Dakota and South Dakota, also.

And in Arkansas, Oklahoma, Montana, Oregon, Indiana, Nebraska and Michigan.

Twenty states total by 1920. Only 28 more to go.

Amazingly, many women joined with men in opposition to the suffrage movement, fearing — like the creators of that postcard — that traditional values and roles in the home would break down with ratification.

Organizers who were twice-disenfranchised — for being born both female and Black — dug in to found the National Association of Colored Women in 1896, whose “Lifting as we Climb” slogan would become a mantra for the movement.

In West Virginia, women began moving mountains to get it done.

Small victories, big defeat

Historians cite the beginnings of the movement here to what was once a hotbed of the Civil War in then-western Virginia.

The West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association was founded in Grafton in 1895 and roared loudly, combining nine smaller, co-existing clubs into one statewide hub.

Seven of the nine, however, didn’t last through that first year.

Still, the women of the movement, stayed standing. Ten years later, in 1905, they finally got Charleston listening. Marquee support from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union helped.

More steering this time, on metaphorical and political roads just as West Virginia’s real ones: Lots of switchbacks, drop-offs, and no roads at all.

A referendum on the issue was crushed by the all-male electorate in Charleston in November 1916. Only two of the state’s 55 counties (Brooke and Hancock) carried it in the affirmative.

Suffragists heavily supported the American effort in World War I, thinking a show of patriotism would move the patriarchy.

And Lenna Lowe Yost, Harriet Jones and Izetta Jewel Brown were just getting started.

The above trio was among the women in the Mountain State that made ratification real.

All three had ties to north-central West Virginia and would continue state and national work for women’s causes.

The activist

Yost, who grew up in Marion County, could have been right out of that postcard. She was a young mother with a toddler in tow when she joined the movement in that benchmark year of 1905, when lawmakers started listening.

She was president of the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association during the flattening of the referendum in 1916.

The defeat only made her work harder, while realizing she needed to stay on task even after the ratification.

Two years after the victory in 1920, she became the first woman to serve on the state Board of Education, where she championed academic opportunities for women. Yost died in Alexandria, Va., in 1972 at the age of 94.

The physician

Jones was busy prescribing her own destiny, as West Virginia’s first woman physician.

The Wheeling medical practitioner who grew up in Terra Alta was approaching her 40th birthday when she joined the effort in 1895.

She helped found the West Virginia Industrial Home for Girls in Salem and the West Virginia Children’s Home in Elkins. She stayed in medicine the whole time and set up a women’s hospital in Wheeling.

Jones was also the first woman to serve in the state House of Delegates, representing Marshall County as a Republican.

Before her death in 1943 at the age of 87, the Washington Post bestowed a title: “West Virginia’s Susan B. Anthony.”

The actress

Brown was a woman of privilege in a poor state.

The New Jersey native had gained fame as stage actress performing in several regional theater troupes when she married William Brown Jr., a U.S. congressman who was also a successful banker and livestock farmer from Kingwood.

After his sudden death in 1916 while in office, she decided to stay in Preston County with her young daughter, where she worked with the movement and eventually wound up as a ranking officer in President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration.

As a WPA regional director, she oversaw women’s relief projects across West Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Kentucky and Ohio.

She was also the first woman south of the Mason-Dixon line to run for Senate, narrowly losing the West Virginia Democratic nomination to Sen. Matthew M. Neely in 1922.

Later in life, she became a radio personality in San Diego, where she also lobbied for the Equal Rights Amendment. She was 95, and still paying attention to politics, when she died there in 1978.

California screaming … and work (evermore)

As a Black woman from Louisiana now living in West Virginia as a single mother, Danielle Walker said she appreciates the history and the hard work that went into the movement, in her adopted home state.

After all, in the Mountain State in 1916, four distinct types were banned from voting:

“Idiots” (on the books).

“Lunatics” (on the books).

Felons (no explanation necessary).

And women (see all of the above).

The U.S. House passed the 19th Amendment in 1918, and the Senate signed off that following year.

It would take 36 of the-then 48 states to make it officially official. In West Virginia, the 34th, it came with drama Brown could surely appreciate.

Jesse Bloch, a senator from Wheeling, cut his California vacation short for the 11th-hour action, riding a train 3,000 miles to Charleston for the special session, so women’s voting rights wouldn’t run off the rails.

He hit town and cast his vote: 15-14. Tie-breaker. It was 16-14, after another senator switched sides.

Which goes back to that postcard: “What would you do in a case like this?”

“Keep working,” Walker said, echoing her earlier answer.

“I think of all the people who came before me,” she said, adding that public service “is different from anything I’ve done in my life.”

Historically speaking, the delegate said, 100 years isn’t that long ago.

And freedoms won, she said, have to stay won.

“As a woman of color, being able to vote and hold office is a privilege,” she said.

“A lot of my work is in registering people to vote. That’s the thing. You’ve gotta vote. A lot of good people worked for your right.”

TWEET @DominionPostWV