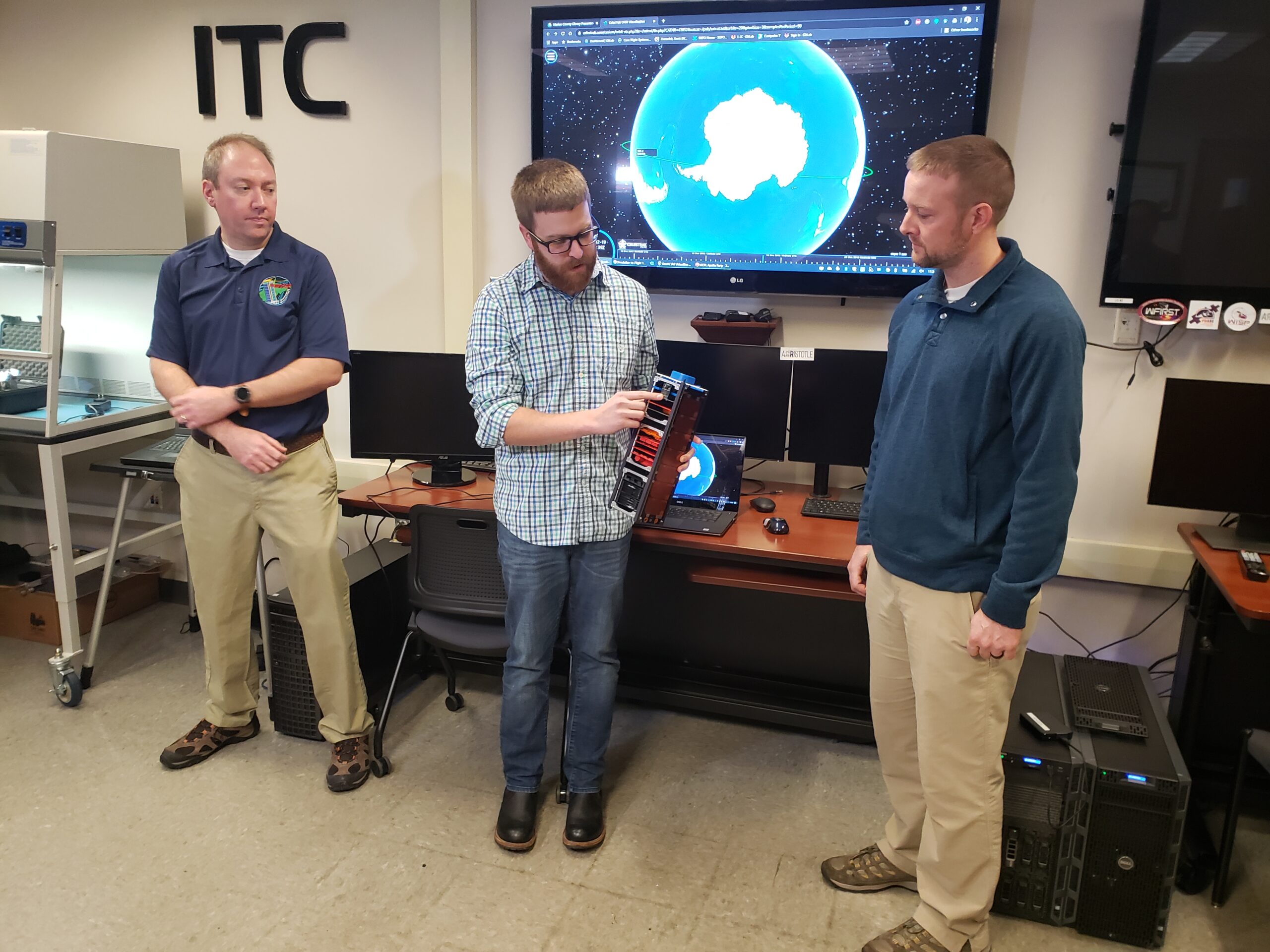

FAIRMONT – West Virginia’s first satellite just passed its first year in orbit and three project engineers met the press Thursday morning to celebrate the project that’s far exceeded expectations and is making a global impact.

“We’re very proud to say we have gone one year in orbit,” said TMC Technologies Chief Engineer and Program Manager Scott Zemerick. “We have successfully hit all of our research and scientific goals. So now any other additional research that we can do, any additional data that we can downlink is just additional icing on the cake as far as this mission goes.”

The satellite is called STF-1 – Simulation to Flight 1 and is a project of NASA’s Fairmont IV&V (Independent Verification and Validation) center, engineered by TMC.

STF-1 was launched Dec. 16, 2018; the TMC team made first contact with it three days later, on Dec. 19; they held their press conference on the anniversary of the first contact.

The typical partial or total mission failure rate for small satellites is 41.3%, he said.

Matt Grubb, lead engineer, said, “We didn’t expect it to live this long.” The typical lifespan for this type of satellite, called a CubeSat, is three months. But after 368 days and more than 5,500 orbits it’s still delivering data for the four studies plugged into its slots. “It may die in the next month, it may die tomorrow, we don’t know. But right now it looks very healthy.”

The pioneering simulation software developed by TMC that is keeping STF-1 circling the Earth every 96 minutes, 500 kilometers up, is called NOS3 and was the 2019 runner-up for NASA’s prestigious Software of the Year award.

NASA selected the project in 2015 for its CubeSat Launch Initiative. TMC is the lead contractor for IV&V’s JSTAR lab, which creates hardware-simulation software through its NOS engine.

JSTAR generally does simulations of big spacecraft to reduce risk and increase reliability of systems.

“The idea for this mission was to take what we do in our day job and roll it into a small satellite, a CubeSat,” Grubb told The Dominion Post in May for a previous story. “We took the simulation technology that we’ve used for all our different missions and tailored it to the small sat world.”

A CubeSat is 10 by 10 by 34 centimeters (about 4 by 4 by 13.5 inches). STF-1 is called a CubeSat because it’s three 10×10 cm cubes linked together into a standardized satellite that can be mounted on a rocket to go into orbit. The rocket will take up a cluster of them and scatter them along its path.

WVU provided the team with four payloads of computer cards to place inside the satellite. One package, from WVU Physics and Astronomy, studies space weather: radiation, solar flares, charged particles plasma. One from the Lane Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering tests radiation-proof LEDs and photodiodes to use for distance measurement and shape rendering. The other two, both from WVU Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, test different means of precise orbit determination. Also inside are the flight computer and the camera that TMC uses to take pictures from space.

Lots of satellites go into orbit, Grubb said, and need software fixes, updates and patches. With STF-1, they wanted to prove that everything could work, with no problems in orbit, through their simulation software. And there’ve been no patches, no updates, and it’s been commanded exactly as done in the simulator. “We wanted 0% chance of failure, 100% chance of success, and the simulator led to that.”

And it’s been relatively cheap, said Justin Morris, NASA principal investigator. It cost just $900,000, including $200,000 for materials. Typical large satellites cost many millions.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland now uses NOS3 for all its missions. The software is open source, so other universities and other government agencies are also using it. And projects in other counties around the globe have downloaded it, they said.

And in Fairmont, Zemerick said, they use the software to train new employees how to command a spacecraft and how to write this kind of successful software.

With STF-1 a success, they said on Thursday, they’re working on planning STF-2, looking for research partners for its payload. Grubb said that STF-2 might be bigger – a 6U, six unit cube, which is more common now. That will depend on what research they line up and the comparative cost, since 6Us are heavier to launch than 3Us.

All three engineers said they’re proud that this has been a West Virginia project from beginning to end.

“It’s just pretty incredible being part of this team,” Morris said.

Grubb, who earned his engineering degree at WVU, said it a new career path for other West Virginians interested in this kind of work.

Tweet David Beard @dbeardtdp Email dbeard@dominionpost.com