Staff, wire reports

OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma has embarked on a multibillion-dollar plan to settle thousands of lawsuits over the nation’s deadly opioid crisis by transforming itself in bankruptcy court into a sort of hybrid between a business and a charity.

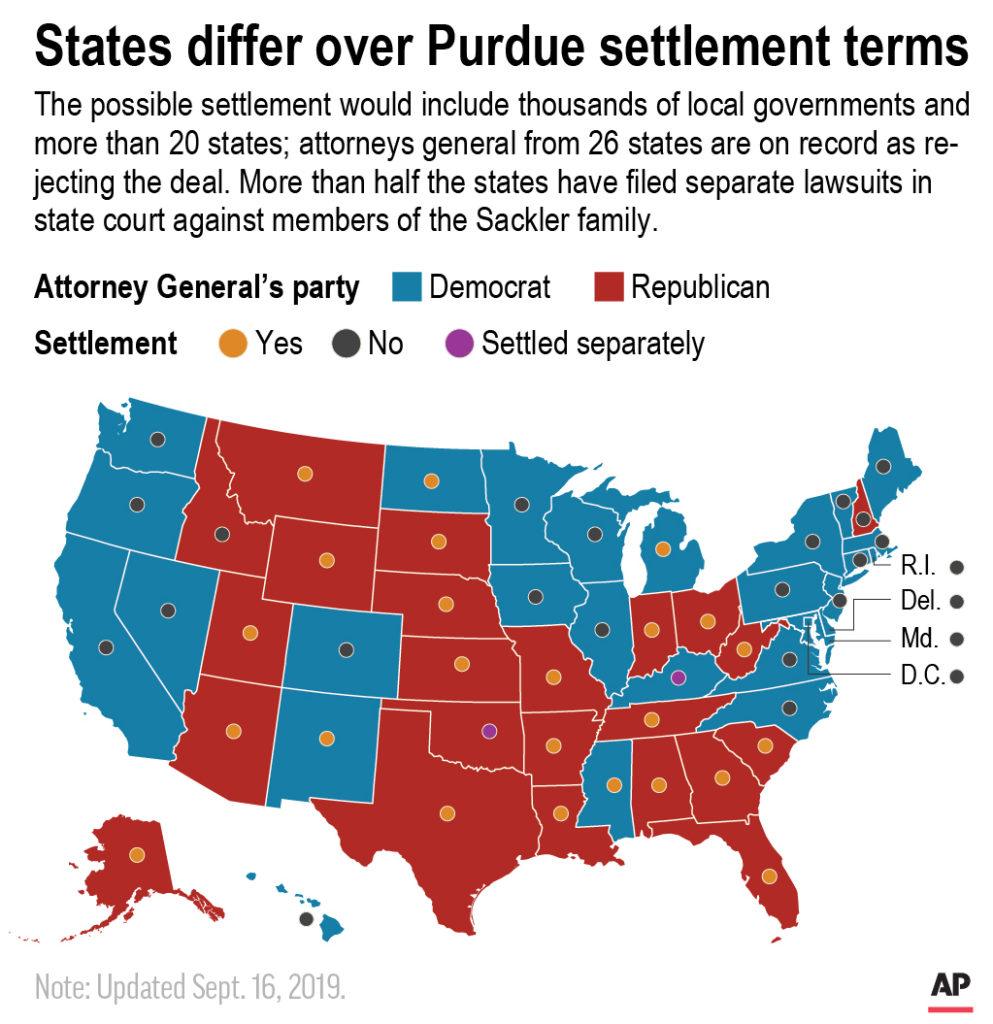

Whether the company can pull it off remains to be seen, especially with about half the states opposed to the deal.

The pharmaceutical giant filed for bankruptcy late Sunday, step one in a plan it says would provide $10 billion to $12 billion to help reimburse state and local governments and clean up the damage done by powerful prescription painkillers and illegal opioids like heroin and fentanyl, which together have been blamed for more than 400,000 deaths in the U.S. in the past two decades.

The plan calls for turning Purdue into a “public benefit trust” that would continue selling opioids but turn its profits over to those who have sued the company. The Sackler family would give up ownership of Purdue and contribute at least $3 billion toward the settlement.

It will be up to a federal bankruptcy judge to decide whether to approve or reject the settlement or seek modifications. If the judge approves it, Purdue said finalizing the settlement will take more than six months, at a minimum. “Prior mass tort cases of this type have taken a year or longer in many instances.”

Two dozen states plus key lawyers who represent many of the 2,000-plus local governments suing the Stamford, Connecticut-based company have signed on to the plan. State Attorney General Patrick Morrisey announced a West Virginia suit against Purdue and the Sacklers in March.

Morrisey said on Monday, “With approximately 2,600 lawsuits filed against them around the country, we expected Purdue Pharma to file for bankruptcy protection. Because we did anticipate this, we put West Virginia on the original framework to keep our position alive and in a place to possibly get what I hope will be a very meaningful settlement. We still intend to hold Purdue accountable for allegations that it aggressively pushed false claims and deceptive practices that helped fuel our state’s opioid epidemic and caused historic, widespread levels of addiction and senseless death.”

But other states have come out strongly against it, arguing that it won’t provide as much money as promised, that the Sacklers are getting off easy and that the family has extracted a fortune from the company and hidden it away in shell companies and Swiss bank accounts.

“The Sackler family sucked billions of dollars out of Purdue and is now throwing the carcass of this drug company into bankruptcy,” said North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein.

He and his counterparts in such states as Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and New York have said they will continue pursuing the company and the Sacklers in court.

The states in favor of the settlement include Tennessee, Texas and Ohio, where Attorney General Dave Yost said the deal is better than other possibilities.

“The settlement puts the Sacklers out of the drug business permanently — not just in the United States, but around the globe. It takes every last dime that Purdue has and billions more from the Sacklers personally,” Yost said.

“The only alternative involves years of additional litigation in the forlorn hope of getting more personal money for corporate conduct.”

In its bankruptcy filing, Purdue denied it is “seeking refuge” and said the settlement is the best way to deliver the most possible money to the public.

The company projected it will spend $263 million this year on legal expenses and other matters associated with the litigation, and warned that the continuing costs will only reduce the amount of money available to deal with the epidemic.

As part of the settlement, Purdue said, the new hybrid company could provide to states and local communities, at no or low cost, opioid overdose reversal medications such as nalmefene and naloxone. Purdue said it has received FDA fast-track designation for nalmefene hydrochloride, a treatment that has the potential to reverse overdoses from powerful synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.

Federal Bankruptcy Judge Robert Drain in White Plains, N.Y., will have wide discretion over the case, including whether the states that don’t like the settlement can press on with their lawsuits. Drain is scheduled to hold his first hearing on the bankruptcy plan Tuesday.

Purdue said that once in bankruptcy, it expects to file a motion for a preliminary injunction to stay all pending litigation against it. This would allow the bankruptcy court to centralize all claims against Purdue and prevent further depletion of assets, while it works toward a final settlement agreement.

“It is likely to change a fair amount by the time when the judge would rule on it,” said Lindsey Simon, a professor at the University of Georgia law school.

Simon said it is also possible the company could switch from Chapter 11 bankruptcy reorganization to Chapter 7 and liquidate the company if the plan looks as if it is falling apart.

One almost certain outcome of Sunday’s filing is that Purdue will not have to face the first federal trial over the opioid crisis. The case is scheduled to start next month in Cleveland. The defendants will be a group of drugmakers, distributors and a pharmacy.

Shaun Wallace, 40, who co-owns three “sober homes” in Worcester, Massachusetts, said he has been in recovery five years from an opioid addiction that started with OxyContin. He said he supports Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey’s decision to continue pursuing the company.

“They were pretty much giving us minor-league heroin and saying it was safe,” he said. “There should be more consequences for that family. Your average drug dealer gets in way more trouble than this family that’s just taken out a whole generation of our people.”