By Chris Schulz & Suzanne Elliott

Former Morgantown Mayor Frank Scafella has seen the good, the bad and the potential of the greater Morgantown area.

As an undergraduate at West Virginia University in the 1960s, Scafella took advantage of the abundant cheap student housing on Willey Street. He also saw firsthand the problems cheap housing caused.

Because houses were bargains, enterprising landlords snatched them up as soon as the properties went on sale. The landlords thought nothing of cramming as many students as possible inside the houses, Scafella said.

They could get away with it because there was no zoning, he added.

“It became a huge mess and a problem,” said Scafella, a retired WVU literature professor, who served as Morgantown’s mayor from 1998 to 2002. “Nobody took care of the houses. If a window or something was broken, you put a piece of plywood over it.”

WVU continued growing and so did the amount of substandard student housing throughout the city and surrounding area. A 1972 Dominion Post article, “Rent at your own Risk,” described some of the student housing around town as “small … poorly lighted,” with “health and safety issues.” But there was no concerted effort to fix the problem.

Much of the problematic student housing was concentrated in the Sunnyside neighborhood, still a favorite off-campus housing option for students. Until the mid-1990s, the neighborhood was the site of an annual, unofficial back-to-school street party that regularly drew thousands of revelers. Houses showed their wear from decades of partying, and city officials were frustrated.

“That was the most-blighted neighborhood in Morgantown,” Scafella said.

During his time as Morgantown’s top-elected official, Scafella butted heads with rental owners in Sunnyside, as the city changed its zoning laws to try to curb overcrowding and poor living conditions. Even after his retirement, Scafella, a Morgantown native, continued with his efforts by becoming executive director of the Sunnyside UP Campus Neighborhood Revitalization Corp.

“The damage that was done was so extensive and so radical that there was just not money available to do the changes that needed doing and the upgrading and so forth. And that’s where the TIF came in,” Scafella said.

What is a TIF?

TIF stands for tax increment financing and is a financing tool that has been used as far back as the 1950s to help fund new and often necessary development in cash-strapped cities, counties and towns across the country.

So how does a TIF work? First, a municipality designates an area within its borders in need of development as a TIF district. Officials then assess the value of all the property in that area and establish a baseline tax before development even begins.

“When a TIF district is created, you lock in … the assessed values of the property within the district, personal and real property on that certain date for the time that the TIF district exists, which can be for a period up to 30 years,” said Jackson Kelly public finance attorney Mark Imbrogno, who has worked on TIFs around West Virginia, including the Charleston Convention and Civic Center TIF and the Fort Henry Center TIF in Ohio County.

“One of the benefits of creating a TIF is that you don’t have to go to the taxpayers to fund a project,” he said.

TIFs are organized around a specific development, so the size of the project tends to dictate the size of the district.

There are no limits to the size of TIFs: Some are just a few city blocks, some cover hundreds of acres, but a “discrete geographic area” must be defined.

For example, the Sunnyside TIF includes not only the traditional student neighborhood just off of WVU’s downtown campus, but also stretches up the hill to the edge of the law school’s campus, just east of University Avenue.

As development of a TIF project advances, the new amenities — be it infrastructure or new businesses — help raise property values and taxes, generating revenue for development.

Property owners will have higher property values and taxes, but the city collects any amount paid beyond the initial baseline and reinvests it back into the area. This way, the increased property taxes actually pay for the development that caused them to rise in the first place.

“You may have some construction noise for a while, but pretty soon your area’s going to get an upgrade. So my property, your property value should increase,” said WVU associate professor of public administration Karen Kunz.

An economic cure-all?

“It was probably, ’98, ’99 that the city began looking around for a way to address blight. One of the ways that became very attractive was the TIF,” Scafella said.

TIFs were quickly embraced by Morgantown and Monongalia County officials as soon as they were made available by West Virginia lawmakers.

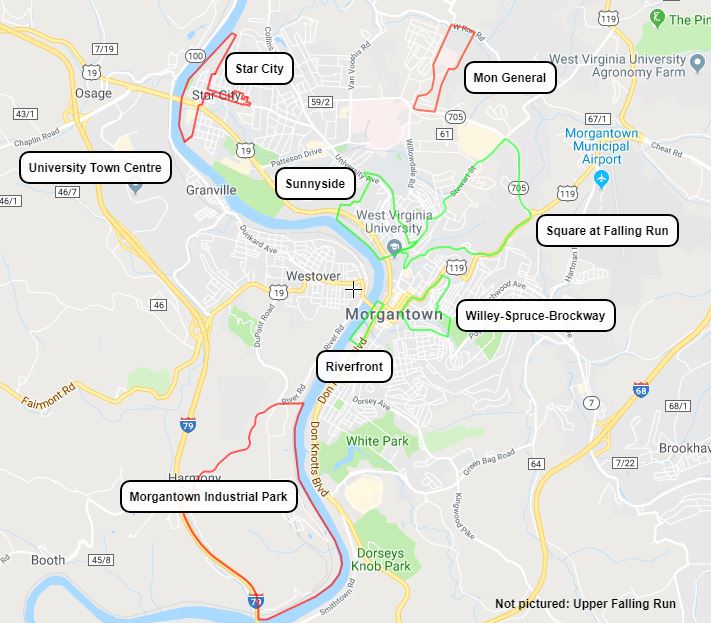

The first two projects approved for the city were the Riverfront and the Square at Falling Run. The Riverfront project funded infrastructure improvements — including a parking garage — that bolstered the existing $200 million public/private redevelopment of the previously derelict waterfront district. Development completed before the TIF was established included the Marriot hotel at One Waterfront Place.

The Square at Falling Run aimed to transform the intersection of University Avenue and Falling Run Road, but fell far short of its objectives. More on that shortly.

The Sunnyside TIF focused on curbing decades of rental owner neglect and student abuse in the neighborhood. It was approved in 2008, the same year Monongalia County was approved for TIFs at the Morgantown Industrial Park and at Mon General Hospital, now Mon Health. Both projects sought the improvement of existing infrastructure, namely roads, in order to promote further development and economic growth.

Recent years have seen a flurry of new TIFs. In 2012, Mon County created the Star City TIF and the University Town Centre TIF.

The Star City TIF addressed aging sewerage and roads by improving infrastructure and preparing blighted plots for future development.

Meanwhile, the University Town Centre TIF has provided the most obvious changes. A new highway interchange allowed the development of the Monongalia County Ballpark, home of the WVU baseball team and the Minor League West Virginia Black Bears.

Not to be outdone, Morgantown created the Willey-Spruce-Brockway TIF in 2014, to help fund streetscape improvements and utility relocations. According to the City of Morgantown the district has, “approximately $375,000 available for ‘pay as you go’ projects,” but work has not commenced and there is no start date set.

In 2015, the Upper Falling Run TIF aimed to install infrastructure to motivate the development of previously unused land.

In total, the Morgantown area is now home to nine TIFs: Five in the city of Morgantown and four in Monongalia County. This is the highest concentration of TIFs in the state by a wide margin.

Why Morgantown?

Morgantown is a city on the rise and one of the bright spots in the state. Between 2000 and 2010, when most of West Virginia was seeing population loss, the city’s population grew by 10%. In the last decade, Morgantown has leapfrogged over Wheeling and Parkersburg to become the state’s third most populated city.

“We don’t have the biggest population, but we have constant influx of university students, parents, spenders,” said Kunz, explaining why TIFs have been so popular with local leaders.

“For a TIF to work, there has to be development or redevelopment, something that’s going to move the needle on the assessed value of the property. Without that … then the TIF isn’t going to do anything,” Imbrogno said.

TIFs helped Morgantown keep up with its growing population, but they have also helped generate more growth. The city’s five TIFs have increased the assessed values of property in their borders by more than $105 million. Coupled with a $190 million assessed value increase in the county, the local TIFs have increased assessed property value in by more than $295 million.

“I’m from Charleston. We just moved up here about three and a half years ago, and I’ve got to tell you the difference in the economies is significant,” Imbrogno said.

TIF drawbacks and failures

There are TIF drawbacks, especially when it comes to rising property values. Just under 13% of Monongalia County’s population is 65 or older, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“If you’re a senior, if you’re living on a fixed income, if you’ve owned your home for 30 years, your mortgage is paid off, but your tax bill is now bigger than your mortgage used to be, you could get priced out of your house,” Kunz said.

Also, TIFs mean municipalities are diverting tax revenue to development, which could affect basic services such as trash pickup and road maintenance. Unlike other states, West Virginia does not fund its schools directly from property tax levies, so the education budget is not impacted by TIFs.

“You’re saying, OK, we’re not going to increase our budget over time unless there’s other revenue from other sources,” Kunz said.

Not every TIF is a success either. While the Riverfront TIF transformed an industrial district like the old train depot into the beloved Hazel Ruby McQuain Park, other TIFs like the Square at Falling Run show problems can occur.

The Square at Falling Run project had the lofty goal to substantially develop the intersection of University Avenue and Falling Run Road. The first phase of the project was the construction of the Augusta Apartments just up Falling Run Road, in 2007.

The next phases of the TIF would have brought radical changes to the intersection, including the leveling out of University Avenue, two new mixed-use high-rise buildings, and a parking garage.

But the development companies in charge of the project, McCoy 6 Apartments LLC, and Augusta Apartments LLC, filed for bankruptcy in 2009 and 2010, respectively, before any of that could be accomplished.

That TIF remains in place. The city of Morgantown still publishes annual reports showing that as of June 20, 2018, there are more than $2 million in outstanding tax increment financing obligations from the issuance of bonds to fund the project in 2007. Any mention of the parking garage or any other building project are absent in reports after 2010.

In response to a request for an update of the TIF’s status, the City of Morgantown clarified that the Square at Falling Run, “is in the debt service phase. Tax increments will continue to be collected until the bonds are retired. In addition to the tax increment revenue, the district receives $120,000 from WVU in payment in lieu of taxes per year for debt service. All construction projects in this district are 100% complete.”

Policing the TIFs

The Square at Falling Run TIF seems to be more of an exception than the norm when it comes to TIFs in the Morgantown area, and that is a testament to the way TIFs tend to be managed in West Virginia.

All TIFs have to be approved by the West Virginia Development Office in Charleston, and the oversight doesn’t end there.

“To use the money for different projects, you have to get approval each time,” Imbrogno said.

Compare that to how Illinois handles TIFs. Illinois and its Midwest neighbors Indiana, Minnesota and Wisconsin are some of the highest-frequency users of TIFs in the country, with the city of Chicago alone playing host to nearly 150 TIFs, as of 2018.

While all TIFs in West Virginia are reviewed at the state level, Illinois only requires that “municipal officials and a joint review board made up of representatives from local taxing bodies” review the TIF proposal.

The other difference is who can create a TIF. In West Virginia, only counties and Class I or II cities — those with a population higher than 10,000 — may create a TIF. In contrast, Illinois places no restrictions on what municipalities may create TIFs.

This level of oversight ensures when a TIF is created in West Virginia, it meets the fundamental requirement for using a TIF, something called the “but for” test.

“There’s one fundamental rule for most TIF projects, the ‘but for’ test. So you have a specific project that you want to do that without the TIF fund cannot be done,” said Jason Donahue of FEOH Realty, which played an instrumental role in the development success of University Town Centre in Granville. “It was almost a funding of last resort.”

In the case of University Town Centre, substantial development had already occurred in the area when the TIF was created. A Walmart, a car dealership and several other stores were in place, but paradoxically their presence was keeping the land at the end of the road from being developed.

“When you tried to describe that property, it was at the end of a road behind Walmart. That’s not a very good selling point,” Donahue said.

The creation of a TIF allowed new infrastructure to be built, including a new road, which made the property more viable for development, he said.

“That’s the ‘but for’ test. I think that some growth would have happened without TIF, but I don’t think the University Town Centre project would have occurred without it.”

The Dominion Post)

The “but for” fulfillment can be seen in nearly all the Morgantown TIFs. Scafella and his former colleagues on city council fought to improve Sunnyside all through the 1990s to little avail. In 2002, the Sunnyside UP Neighborhood Revitalization Corp. was founded, but it wasn’t until 2008 when the area was granted TIF designation that real improvements began.

Streets were cleaned and repaved, alleyways were beautified and, most notably, the University Place high-rise apartment building was constructed, with a Sheetz at the ground floor.

The “but for” of a project is not always obvious, as in the case of the Riverfront TIF.

“It wasn’t going well,” Scafella said of the Riverfront development before the TIF. Much had been built, but there was still something missing.

“The university was able to get a lot of the infrastructure done by the tax increment financing funds,” he said.

“But for” the TIF, infrastructure that includes the parking garage next to Waterfront Place would not exist. Today, the multi-level parking structure allows residents to enjoy the trail and patronize the many restaurants and other businesses in the Waterfront District.

The TIF funded much of the infrastructure in the area that even today allows people to enjoy the trail.

“It’s a community asset,” said Morgantown resident Gerry Katz on a recent summer evening, as she sat contemplating the rail-trail with her husband and a friend.

“Everybody’s out here walking with their dogs, their kids in strollers, on bikes, on Rollerblades, talking to other people,” she said. “It’s the best thing that ever happened to Morgantown.”