MORGANTOWN, W.Va. — Two West Virginia University researchers have begun a project to help power plants use less water. While it sounds counterintuitive, they’re doing it by combining wastewater from power plant cooling towers with wastewater from fracking operations.

The project is in its infant stages, funded by a $400,000 Department of Energy grant and launched last month.

“If we can combine two waste streams and get a more desirable product at less cost, really that’s our ultimate goal here, said Paul Ziemkiewicz, director of WVU’s Water Research Institute.

Ziemkiewic came up with the idea “that saves fresh water resources and makes better use of wastewater rather than simply disposing that water in deep injection wells and other things like that, that are expensive and have environmental consequences.”

Lance Lin, a civil and environmental engineering professor and principal investigator on the project, said, “The beauty of this approach is you solve two problems with one integrated solution.”

They point out that the power industry is a huge water user: nationally, second after agriculture, but in West Virginia by far the largest.

Thermoelectric power plants – fired by coal, gas or nuclear power – use water in heat exchangers to cool the high-temperature steam that spins the turbines. The warmed-up water then flows into cooling towers where the heat is released. Some of the water also evaporates – seen in the while plumes that rise from the towers.

But much of the water is recirculated to keep cooling the turbines. And the natural salts in the recirculated water concentrate to a point where they could foul the cooling system. That water is called blowdown water. It has to be treated before it can be further recirculated or returned to the river it was drawn from.

That’s where the “produced water” from fracking sites comes into play. Produced water is what comes back up from the gas well after it’s drilled – maybe 500,000 to 1 million gallons per well.

Produced water contains what are called divalent cations (pronounced cat-ions): magnesium, calcium strontium, barium and radioactive radium.

The cations would cause scaling on the cooling tower plates, Ziemkiewicz said. But blowdown water has carbonates and sulfates needed to precipitate them out of the solution.

The combination produces clean water to recirculate – minimizing the need to constantly draw form a river – along with two beneficial byproducts: chlorine to disinfect the cooling system and 10-pound brine that has several industrial applications.

For their project, Lin and Ziemkiewicz are obtaining produced water from WVU’s Northeast Natural Energy research well at the Morgantown Industrial park and blowdown water from the Longview Power plant.

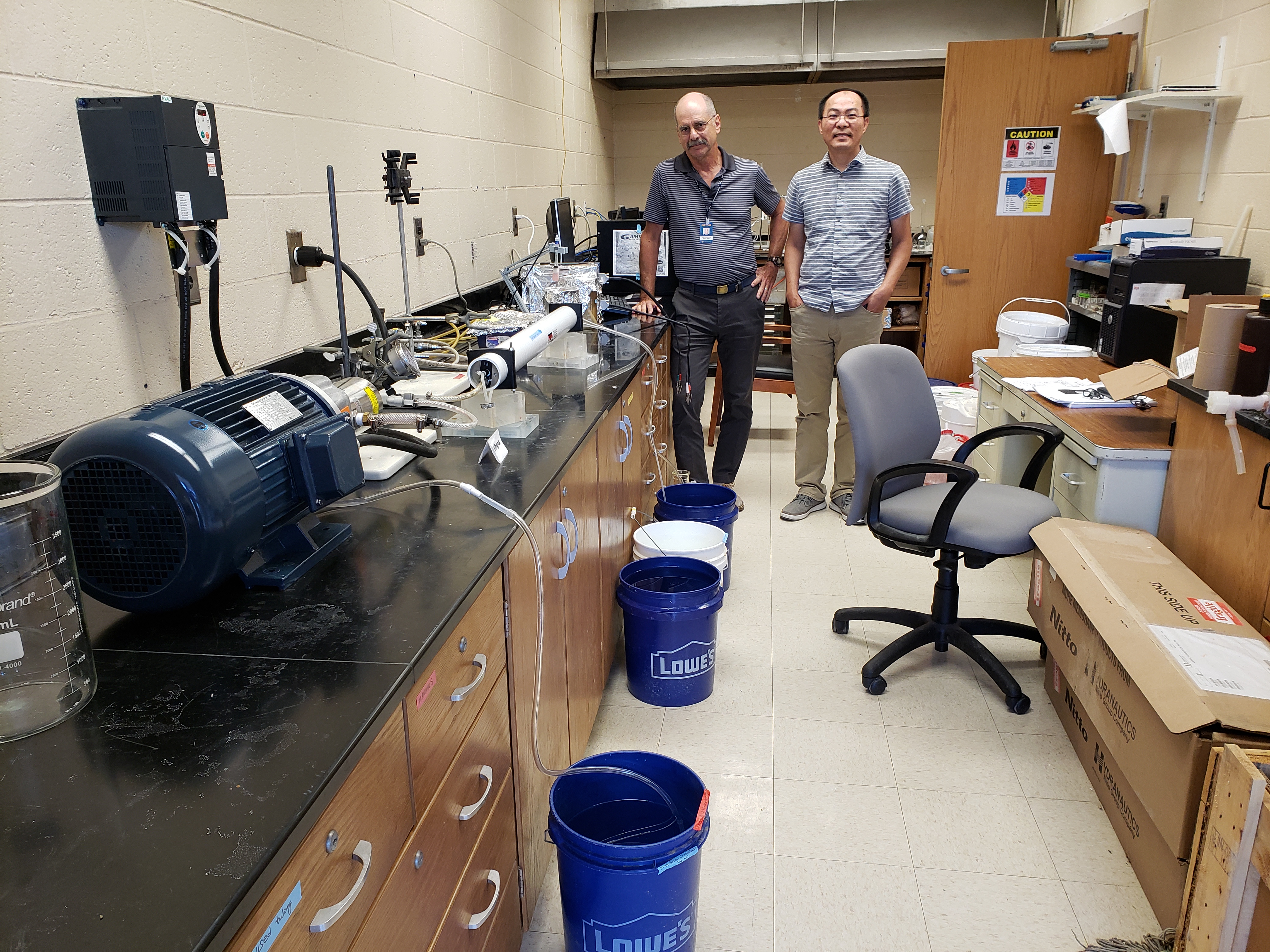

They’re still in the lab testing phase, Lin said. They’ve tested treatment units, mixing the two waters.

“Just mixing them gives some degree of treatment,” Lin said. They’ve determined the mixing ratio to get best results from the free treatment and are now testing to further remove divalent cations from the mixture. They have two more treatment units to test.

They have a good year or two of test individual treatment units, integrating them into the process and developing a system design, Lin said.

It’s not something that could work everywhere a power plant sits, Ziemkiewicz said, but where power plants and gas plays co-exist. As it happens, West Virginia has a high concentration of coal- and gas-fired plants sitting atop the nation’s biggest natural gas play.

“If you’re going to start anywhere, this is the place to start,” he said.

Tweet David Beard @dbeardtdp and email dbeard@dominionpost.com